Booker T. Washington’s Connection to Rye

While doing research for a biography of John E. Parsons some years ago, I found a letter to him from Booker T. Washington in the archives of the Rye Historical Society. Washington, the noted African-American head of the Tuskegee Institute, had written in 1904 to Parsons, a noted lawyer and longtime Rye resident, to express appreciation for his gift to Tuskegee of $500 (equivalent to almost $27,000 today).

Parsons and Washington had met in Stockbridge Mass., the town next to Lenox, where Parsons had a summer home. An article in The New York Times on Sept. 4, 1904, reported that “Booker T. Washington is a guest of Alexander Sedgwick of New York at Mr. Sedgwick’s country house. Several prominent Stockbridge and Lenox cottagers are to meet and lunch with Mr. Washington Monday afternoon, including John E. Parsons….”

Born into slavery in 1859, Washington had graduated from Hampton Institute. After teaching there, he left in 1881 to start a new school in Tuskegee, Ala., whose primary mission was to train African American students to become teachers. He remained head of Tuskegee until his death in 1915 and built it into a leading educational and vocational institution.

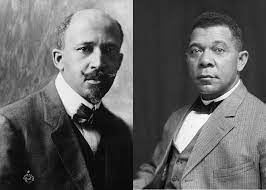

Washington also achieved a national reputation because of his skills in improving race relations and developing job opportunities for blacks. Although he was criticized by W.E.B. Du Bois and other black leaders for being too “accommodating” to whites, Washington’s success in raising funds for Tuskegee and other black schools gave him national prominence.

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt shocked many Americans when he invited Booker T. Washington to dine with the first family in the Executive Mansion. Not only was it the first time that an African American (and former slave) had dined at the White House, but it demonstrated Roosevelt’s high personal esteem for Washington.

Later, I discovered an account in an early issue of The Rye Chronicle of an address made by Booker T. Washington at Rye Presbyterian Church on Jan. 26, 1910. It reported, using a term for black people that went out of use a long time ago, that, “Despite inclement weather, eight hundred people were present…on Wednesday evening to listen to the great colored speaker, Booker T. Washington, on the occasion of his first visit to Rye.”

The reporter noted that “Mr. Washington’s itinerary takes in the large cities,” and that “his coming to Rye was a compliment to the village pastor and the trustees of the local church,” which included John E. Parsons.

Just two days before his visit to Rye, Washington had addressed an audience of 2,000 at a meeting at Carnegie Hall, chaired by former New York City Mayor Seth Low. The purpose of that meeting was to screen a film, entitled “A Day at Tuskegee,” which showed the students and facilities of the Institute and Washington’s program of “industrial education” in action.

Although the film was not shown at the meeting in Rye, the Chronicle said that Washington described Tuskegee’s “remarkable growth from an old cabin to its present size, having 96 buildings and three Thousand acres of land, all of which were erected by the scholars themselves…. More than 6,000 colored people have been graduated from Tuskegee, and under the practical training received there, they are doing much to solve the race problem in the south.”

The account went on to comment, using another term for black people that is no longer used, that, “In describing the relations of the black and white man as neighbors, Mr. Washington was a consummate diplomat by the skillful manner in which he handled that thorny subject. He had nothing but praise for the white man’s treatment of his black neighbor, although it is a well-known fact that our treatment of him is by no means as praise-worthy as it might be. No open mind can hear Mr. Washington without feeling a desire to help him and his worthy cause. This help need not necessarily reach Tuskegee; it can be directed to good advantage to our nearest negro neighbor.”

There was no mention in the article of the rivalry that then existed between Washington and DuBois and his criticism of Washington’s approach to race relations and his emphasis on practical rather than academic education..

Washington countered that having risen to leadership from slavery, he represented the masses of black people far better than “artificial” men like Du Bois (the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard). He also had achieved great support for his educational programs by cooperating with both northern and southern whites.

There is no better time than Black History Month to learn more about the conflicting views of Washington and Du Bois on how best to champion the cause of civil rights for black people in America. A good starting point is www.biography.com/activists/web-dubois-vs-booker-t-washington.

Image:

W.E.B. Du Bois (left), and Booker T. Washington