By Tom McDermott

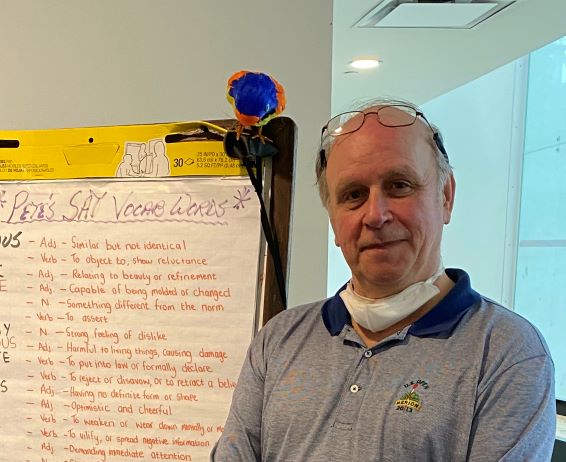

Entering the squash facility at Apawamis Club, a visitor immediately notices that the walls resemble a classroom more than a place that, season-after-season, produces some of the finest young squash players in the country. For 30 years, young people, as well as adults and seniors, who arrive for lessons and games have seen an array of framed inspirational sayings, lists of SAT-word definitions, and photos of previous generations of players on display.

Currently, one of those is a copy of a “Pete’s Point of View”, the “Pete” being Apawamis Head Squash Professional Peter Briggs. Reading it, you would not be surprised to learn that Briggs, in addition to once being captain of Harvard’s squash team, a national squash champion, and legendary left-wall doubles player, was a Classics major.

Briggs writes, “I am an educator, not a retailer. I believe in personal relationships, not transactional ones,” a bold statement, considering the pervasive recruitment of high school players to attend the country’s top colleges.

Briggs believes this system is going in a bad direction. “Health and mental well-being of young athletes suffer. Specialization in one sport and the commoditization of the athletes creates wear and tear. It can be hard for me, being in the middle of it.”

His goal is to develop the whole person, on and off the court. To build self-confidence and to empower his charges. He is most proud of the number of team captains he and his staff have developed. For Briggs, the fact that the captains often play in the middle of a lineup demonstrates that character and values make the difference.

This ethos began for Briggs with another squash legend, Jack Barnaby, who coached more than one generation of players at Harvard. “Barnaby was a coach and life mentor,” says Briggs, “He told us all, Day 1, ‘Put your ego in your back pocket.’ For him, it was all about the pupil. Some days we just talked, and I learned something new every day. Barnaby was a vehicle to build character. You were taught that you were not just playing for yourself, but for the team, the school.”

Briggs is working with his third generation of players at the club. Not all players are motivated to achieve top-ranking and championships. The player chooses their level; Briggs and staff will help them get there. A surprising number of players return to the fold, raise families in Rye, and bring their children to Briggs who says, “They can come back after college and feel a part of something.”

Speaking with Briggs or reading him, he sometimes sounds like a teacher of Eastern philosophy, without pretense. “Photos of present and past generations of players give us a sense of … continuity and legacy. They are reminders that we are part of something greater than ourselves that has a value and a shared history.”

Recently, I had an opportunity to spend time with Briggs at his home, where he and his wife Di hosted a few friends for his 70th birthday. After dinner, seated on his porch, Briggs the Classics major was in rare form, lobbing tough questions about Greek classics and myths to the table, particularly two young high school-age girls, neighbors of his. Far from being bored or put off by his challenge, they not only engaged in the competition, but scored a surprising number of points on the master.